As I was about to complete high school, I remember watching footage and seeing photos of jubilant people clambering over what was once the Berlin Wall and taking chunks of cement as souvenirs. At the time I did not understand what this really meant for the people of Germany or what they had been through in the previous four decades. My recollection is only the smiles of joy and the moments of reconciliation. Little did I know that, in my life time, I would see another wall, twice as high and four times longer, constructed for similar reasons in another part of the world. In my travels to Israel and Palestine Territories last August I saw the monstrous wall of separation and heard stories of its impact upon the people.

The ‘Separation Wall’ (as called by the Israeli people) or the ‘Apartheid Wall’ (as called by the Palestinian people) was first proposed in 1992 after the murder of an Israeli teenage girl in Jerusalem.

In October 1994, after an outbreak of violent incidents in Gaza, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin said, “We have decided on separation as a philosophy. There has to be a clear border.”

The first section of the wall was built that year. The Israeli people argue that the wall is necessary to protect Israeli civilians from Palestinian terrorism. It is true that since the commencement of the building of the wall suicide bombings have decreased in these areas. Some would argue, however, that this has nothing to do with the wall, but is more about the increased pursuing of Palestinian militants.

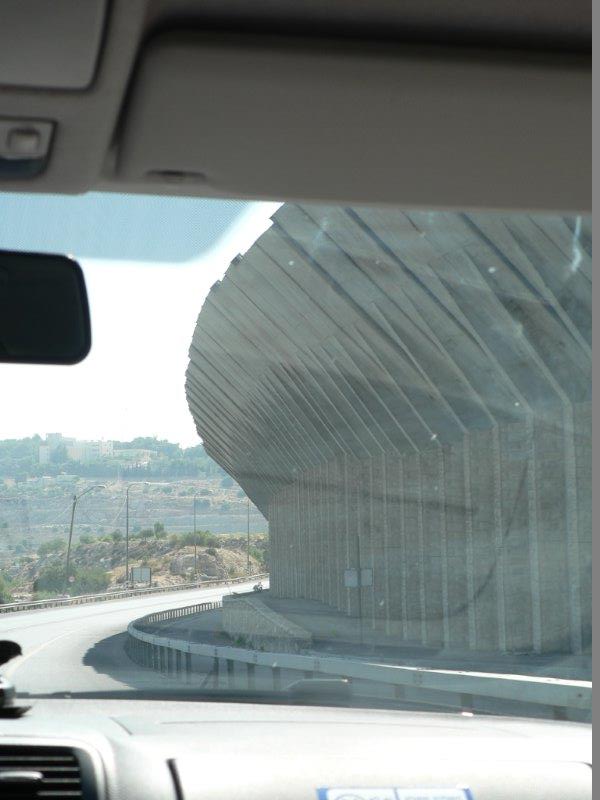

The wall was to follow the 1949 Armistice Line, known as the ‘Green Line’. Today, however, the barrier diverges from this by anywhere between 200 metres to 20 kilometres to include Israeli settlements that are within the West Bank on the Israeli side. Most of the barrier consists of a multi-layered fence system, but in more urban areas this is being replaced by an eight metre high concrete wall. My feeling when first seeing this wall was its imposing nature and the fact that you are completely separated from whatever may be on the other side. The wall hides these neighbouring people completely.

Only 20% of the wall actually falls on the Green Line and in some cases Palestinian towns are almost completely encircled by the wall. In July of 2009 the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion that the construction of the wall beyond the Green Line was a violation of International Law. In a few instances international pressure has led to the route of the wall being reconsidered, but these are certainly a minority.

It is not uncommon to see images of effective graffiti on the Separation Wall, particularly from around Bethlehem. Leading up to Christmas there were many clever cartoons and political statements across social media raising awareness about the wall and its impact upon the people. However, being so removed it is difficult to fully appreciate the effect of such a barrier. On my recent trip, we travelled to Bethlehem with a Palestinian taxi driver. He was not afraid to tell us his story and how the wall had affected his life and the lives of his friends. His account of the struggle confirmed and brought to life what I had read about the Palestinian people and their plight.

The Palestinian people describe the construction of the wall and the associated restrictions upon their life as the formation of ghettos. The building of the wall has separated Palestinian people from medical, cultural, religious and educational services. To access these facilities, Palestinian people must enter and exit through guarded checkpoints. According to our taxi driver, the waiting time at these checkpoints can vary from a few minutes to many hours. There appears to be no rhyme or reason to how long the wait could be. This level of control creates an impossible situation for those trying to gain an education or hold down a job beyond the wall.

The wall has also been built in such a way that much Palestinian livelihood and land has been lost. The people living in the path of the wall and its 60 metre exclusion area at times are only given a few days’ notice before their shops, olive trees or homes are destroyed. In November 2013 alone, 786 olive trees were uprooted to make way for the further construction of the wall. Despite the loss of beautiful trees, this is the destruction of the income of Palestinian families. Farmers find themselves with no access to their agricultural land which now falls on other side of the wall. The construction of agricultural ‘gates’ in the wall is still no guarantee that farmers will be able to access their land. The existence of the ‘Absentee Property Law’ gives the Israeli government the power to take and use land that has been ‘abandoned’ due to people fleeing during times of conflict. In November 2013, almost 525 hectares of land were confiscated from Palestinian people.

Water is a scarce resource in Middle Eastern countries as can be seen from the 1967 Water War. In the building of the wall beyond the Green Line Palestinian people have been cut off from major fresh water sources that now fall in Israeli territory. The denial of such a basic necessity in life is an act of control and power that oppresses the people in more ways than we will ever know.

Living in a country where we are often working towards overcoming the isolation felt by distance, it is difficult to conceive the impact of being completely separated from neighbouring communities. Many have asked if this is a temporary measure to curb violence. At over 2 million USD per kilometre it does not seem that the construction of this wall could be temporary. I can only hope and pray that in my children’s life time they will witness the tearing down of this wall, the smiles of joy and the tears of reconciliation as neighbours meet and learn to live together once more.

Cathie Lambert