Why did Jesus die?

Many of you will immediately respond (wondering why I ask the question) “He died for my sins.”

But I’d suggest that we Christians need to stop and think about this a while, for at least a couple of reasons.

Firstly, if you respond with this answer when asked what is Easter all about by someone who is not ‘churched’ what would they make of it? What do you actually mean? “Jesus died for my sins” is actually a shorthand phrase for a lengthy theological account that many of us would have trouble explaining.

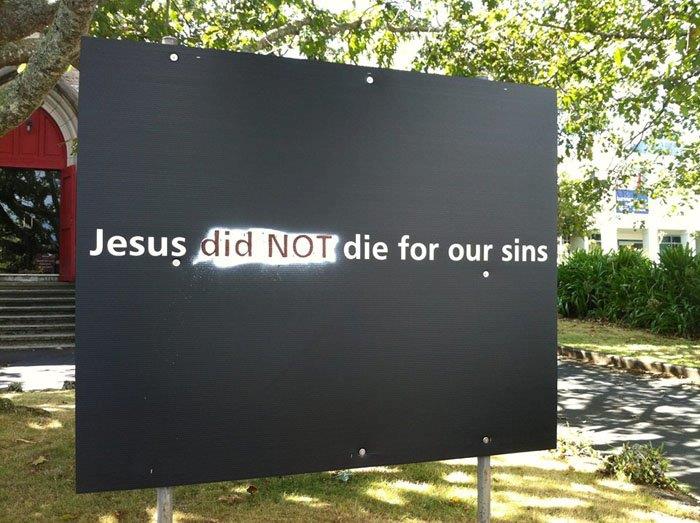

But secondly, as the billboard outside St Lukes, Auckland says “Jesus did NOT die for our sins.”

We actually know very little about the death of Jesus. We do know that he was crucified, probably around the Passover, in Jerusalem, by order of the Roman prefect of Judea, Pontius Pilate. It’s not much, but it tells us something significant about Jesus and why he was killed. It tells us that his executioners were Roman, not Jewish. It tells us that his crime was sedition against the Roman state. It tells us that he was regarded by his executioners as a peasant nobody who had the temerity to challenge the Roman ‘peace’.

Jesus died because he was a victim of Roman rule and authority. His death was used as an example, to intimidate others who might think or act similarly. Because simply, Roman rule was established and maintained through violence and intimidation. Rome had expanded across the known world by relentlessly waging war. But military force alone was not sufficient. Two other powers combined to make the empire possible: patronage, and the power of theology.

A patron maintains power by using their power to the advantage of those next down on the pecking order who then work on behalf of their patrons interests. They are patrons of those on the next rung down the social ladder and so on. The pinnacle of patronage was the emperor.

The second power was theological (yes – God talk). Because the Roman ‘peace’ was seen as a gift of the gods. Augustus was seen as nothing less than a messenger from the gods – God’s own son – and the people were required to demonstrate their loyalty to their god – the emperor.

Enter Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus was marginal to the empire just like those he associated with – fisherfolk, ordinary women and prostitutes, lepers, and beggars. They belonged to a category called ‘expendables’ – much like the dalits of India. Jesus spoke and created stories about another empire – an empire that included expendables; an empire that was not just in the future, but here and now. An empire that would be achieved through love not war. This sort of talk was a crime. This was talk that got you killed.

Jesus imagined life outside the realm of patron-client relations, a different empire where there were no hierarchical relations. Instead care, nourishment and support were to be offered in a context of love, equality and mutuality. Jesus talks about this alternative empire all the time – he called it the kingdom of God or the kingdom of heaven.

His was a dissenting voice in a culture that did not tolerate dissent.

The death of Jesus was perhaps, the inevitable result of that dissent, especially given his arrival in Jerusalem at Passover. Passover was the annual Jewish celebration of liberation, commemorating the end of the Egyptian captivity. Given that many Jews experienced Roman rule as captivity, trouble was always expected. The Roman occupiers knew how this festival could be construed – the prefect came from his seat in Caesarea with additional troops to quell unrest.

Whatever happened in the temple in Jerusalem, Jesus did not live long afterwards. He was arrested. His trial would have been brief, if there was a trial at all. He was, after all, a nobody, an expendable. Jesus was an expendable who cried out against an empire to which he mean nothing except as a rebel – and so he was crucified.

His followers, belatedly understood his invitation to see the world differently. When they decided to continue on with what Jesus started, they knew they too were turning their backs on imperial culture.

What does it mean for us to follow this Messiah? Does it mean that rather than relying on some personalised, individualised notion of ‘salvation’ it means that we are to embrace a vision of a future that is counter-cultural, counter empire? What might that look like? Must we be willing to embrace ideas that seem foolhardy, and embrace the fools that espouse them? Do we have the courage to face the consequences of realizing how inhospitable the world remains to Jesus’ vision of God’s empire, and live out Jesus vision in spite of the consequences?

Rev Karyl Davison (with thanks to Glyn Cardy, St Luke’s Auckland). Karyl is a minister at the Eaton/Millbridge Project.