St Andrew’s on St Georges Terrace, is the church where my parents were married in 1943 and where I went to annual church services as a PLC student. Probably the last service I attended, the church was packed for the funeral of Heather Barr, principal of PLC and lifelong St Andrew’s member who died suddenly and unexpectedly in 1989. Those are my memories of St Andrew’s.

I’ve begun this article with personal memories because in my research I have found plenty of information on the building but very little on the people who worshipped faithfully each week, whose life milestones of baptism, marriage and death were celebrated there. And yet it is people who are the church, not the building.

The birth of St Andrew’s began with the arrival of Rev David Shearer. Through the joint action of the colonial committees of the Established and Free Churches of Scotland, he was commissioned to plant the ‘blue banner’ of Presbyterianism in the colony of Perth, Western Australia. He arrived at Fremantle with his wife, Margaret, and seven children, plus governess, on 1 October 1879. Not one to waste time, he held his first service ten days later in St George’s Hall, Hay Street. His sermon was preached from the deck of HMS Pinafore, the set of the Gilbert and Sullivan musical comedy performed there the previous night.

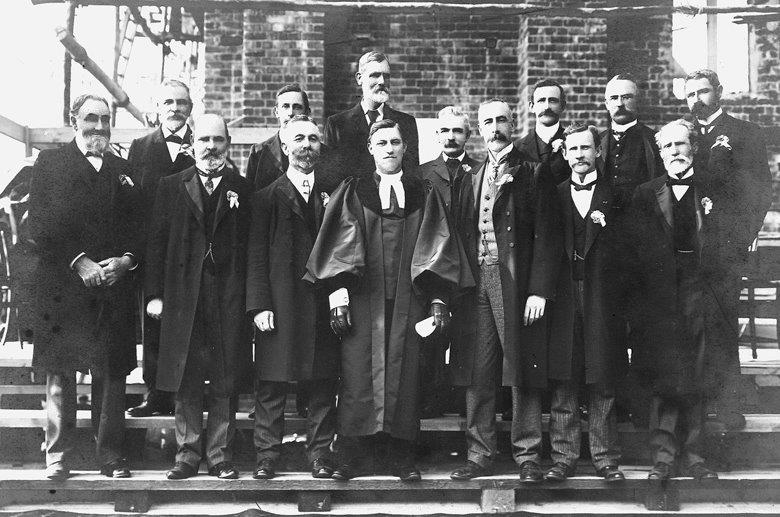

Front row: Messrs W H Meek (Elder), J Coultas, Jas Longmore (Elder), Rev A S James, John Nicholson, John Stains and J Marshall.

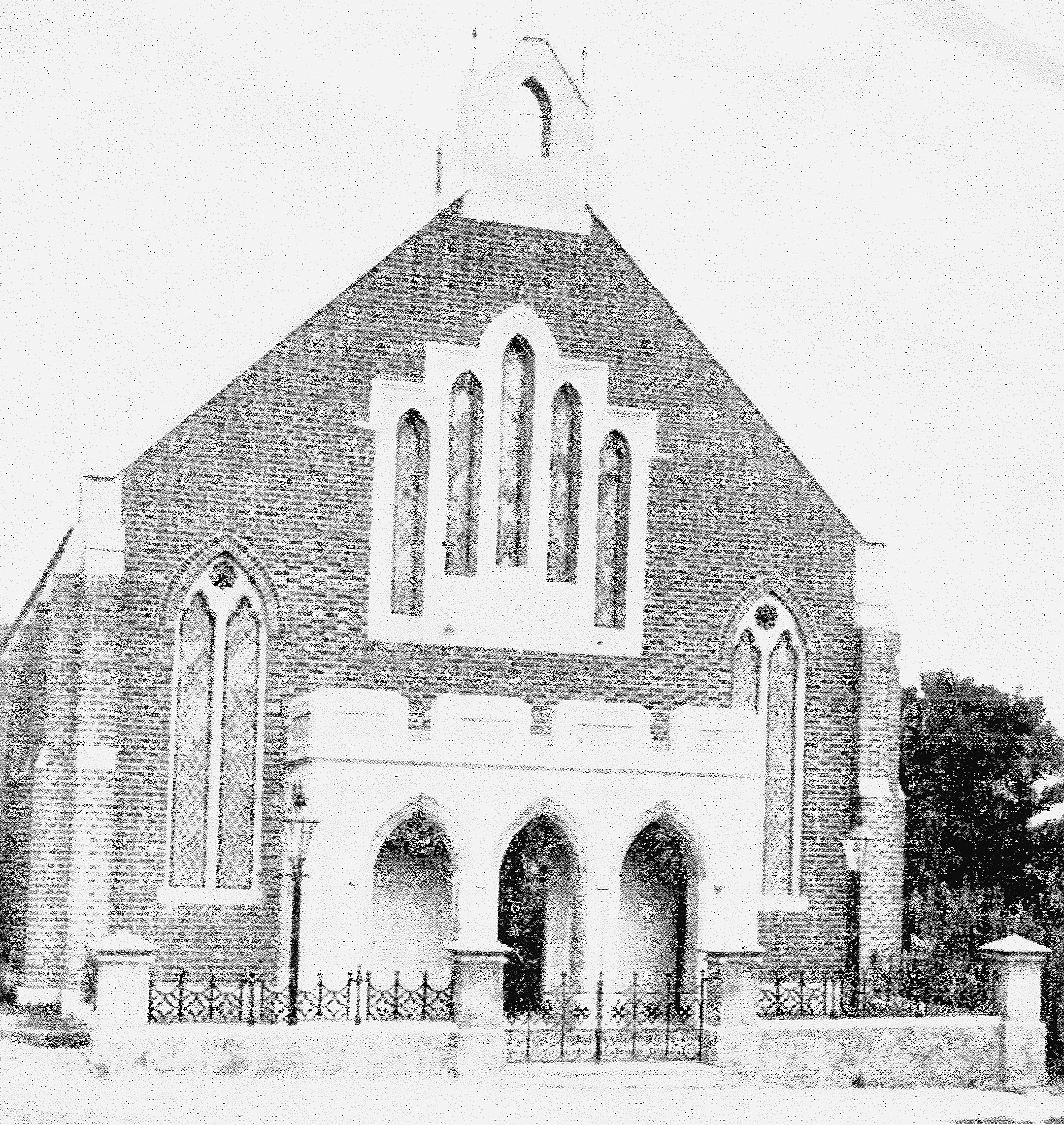

Determined to fulfill his task of fostering the seed of Presbyterianism in the colony, he applied for and gained crown land in 12 country towns and Fremantle. The land allocated in Stirling and Beaufort Streets in Perth was deemed too far from the centre of things. Shearer therefore dug into his own pocket (fortunately he was a man of means) to the tune of £800 for land in Pier Street. Through his own personal exertions he then raised £600 for the building of a church. Seating 300 the Perth Presbyterian Church at 10 Pier Street was dedicated on 1 August 1882 – less than three years after his arrival. Ten years later, the stone font, the workmanship of inmates of Fremantle prison, was presented to the congregation. In February 1886 it would be the first church in Perth illuminated by gas lighting.

In those early years a popular occasion for the whole Perth community were the afternoon tea and concerts held annually in the Town Hall to mark the anniversary of the arrival of the Rev David Shearer with his family, and the opening of the church.

David Shearer’s work, as well as church ministry, focused on education within the colony. His vision was for a broad based Christian education and, although he did not live long enough to see it realised, in 1897 the first lessons of what would become Scotch College were held. Presbyterian Ladies College can also trace its formation to a meeting in 1915 of St Andrew’s men in the vestry of the church.

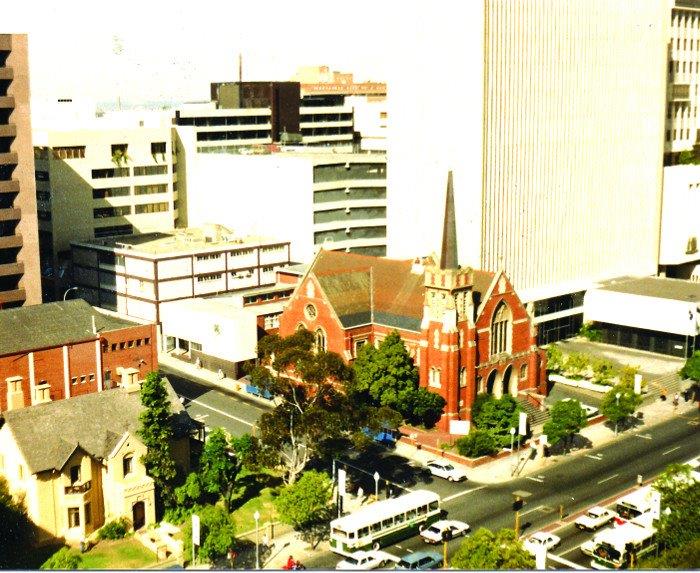

With a surge in optimism throughout the community at the start of a new century, plus a financial boom thanks to gold discoveries, the church fathers decided a new church, able to seat 800, should be built on the corner of Pier Street and St George’s Terrace. The governor, Sir Frederick Bedford, laid the foundation stone of the building we all know on 1 September 1906. A year later the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of WA met in the ‘commodious new church’. Rev John Ferguson, Moderator of the Australian Presbyterian Church and visiting from Sydney, remarked, ‘The Presbyterians in the east think the Presbyterian ministers in Western Australia, as a whole are the bravest and most resourceful men the Church possesses in the whole continent of Australia.’

For the next 70 or so years the Assembly would continue to meet in St Andrew’s.

It had been in 1891 that the church decided, rather than be known as the Perth Presbyterian Church, to adopt the name of the patron saint of Scotland, St Andrew – not surprising, as the root of Australian Presbyterianism was Scottish. St Andrew’s became the ‘high kirk’ for those with a Scottish heritage. Until quite recently this Scottish connection was fostered with special ceremonies to mark Burns Night, the Kirkin’ o’ the Tartan, Scottish Nights, and St Andrew’s Day. It was also the spiritual home for the 16th Battalion (Cameron Highlanders of Western Australia).

In 1886 improvements to the original Pier Street church included the installation of an organ as well as gas lighting. The organ was moved to the new church in 1906 but it proved inadequate for a building of that size. It was sold to the Anglican Cathedral in Kalgoorlie and money was raised, mostly by a series of fairs, for a new organ to be dedicated as a memorial to those who had died in the Great War of 1914-1918. The organ was installed in the east transept and dedicated in 1924. In the 1950s it was moved to the front of the church and its pipe frontage and casework was covered by a screen formed by a large wooden cross of native timbers. Admired by many it was disliked by others who claimed it made the church interior too dark. Although acoustically designed the screen nevertheless muffled the organ and much of its clarity was lost. With a rebuild in 1984 the organ was once again sited in the east transept, although the screen remained in place.

A major milestone for the people of St Andrew’s was their decision to join with the Methodist Church and other Congregational and Presbyterian Churches to form the Uniting Church in Australia in 1977. A consequence of this was the problem faced by city congregations in all states – the Uniting Church found itself with three ‘cathedrals’ in each capital city.

Unfortunately the canny Scotsmen of St Andrew’s had not been as canny as their Congregational and Methodist brethren in ensuring they had sufficient land and positioning to enable them to develop lucrative commercial property resources. Over the years, several ideas were put forward, plans drawn up and approved for the development of the sites occupied by Westminster House and McNess Hall, both adjacent to St Andrews. None of these were able to be realised.

With falling congregation numbers – common across all mainstream Christian denominations – and the rising maintenance issues of an old building, heritage listed since 1980, St Andrew’s struggled.

In the 1990s some essential maintenance work was carried out under the direction of heritage architect, Ian Hocking. But it was a case of ‘too little, too late’.

In June 2009 St Andrew’s was deemed unsafe and closed. Quotes for the repair of the roof and ceiling would have cost at least hundreds of thousands of dollars. The congregation moved their worship services to McNess Hall and continued to meet regularly.

With reluctance and after careful prayer and consideration, the Uniting Church Synod agreed St Andrew’s, Westminster House and McNess Hall should be sold. In taking this decision the Synod was aware it would impact, not only on St Andrew’s congregation, but also on the wider Uniting Church, and the people of Perth. For almost 110 years, St Andrew’s had played a role in the lives of generations of Perth people. It was a sacred space for quiet prayer and communal worship, and a place for commemorating important life milestones and community events.

Churches no longer used as places of worship are a fact of life in today’s world. Whenever and wherever a church building is closed, it is a time of pain, grief, and loss for those connected to it, however distantly. Much emotion, history and memories are wrapped up in bricks and mortar.

Because it is heritage listed, St Andrew’s building will remain as a Perth landmark. The building has left the Uniting Church family, but its people have not. The congregation will continue as a worshipping community gathering each Sunday at the small church within the grounds of the East Perth cemetery, where Rev David Shearer lies. Somehow that seems fitting.

Judith Amey