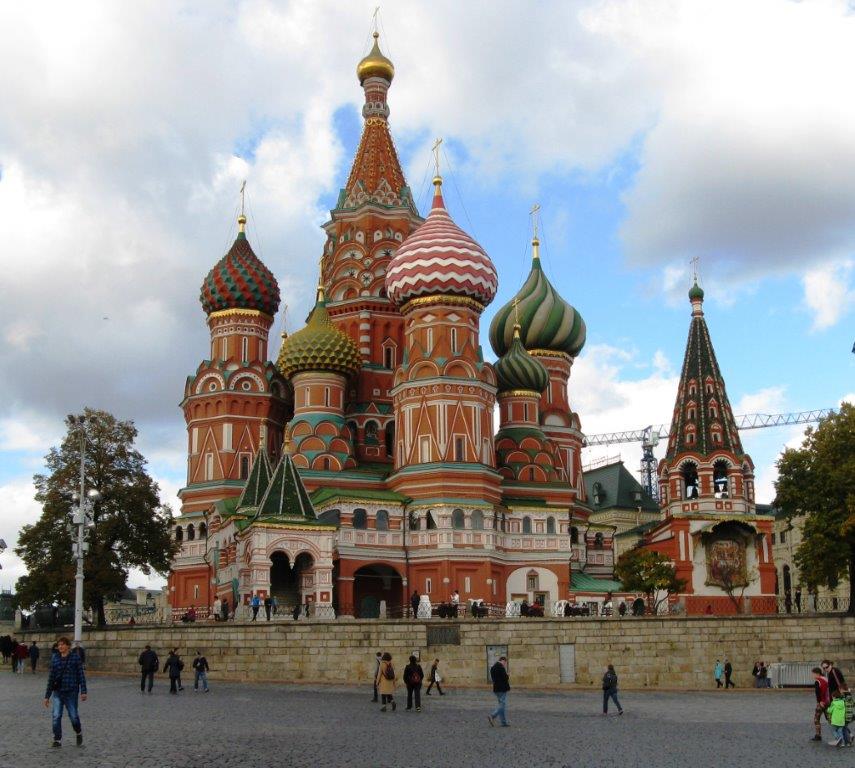

In the last week of September a very special event took place in Moscow. For the very first time, a hundred scholars came together in Russia to focus on the New Testament and its meaning for faith.

The largest contingent came from Russia itself, predominantly from the mighty Russian Orthodox Church. Alongside them were Orthodox scholars from a range of Eastern European countries, including Greece, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Belarus, Ukraine, as well as Catholic and Protestant scholars from Finland, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Hungary, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Britain, USA, and Australia.

I made the journey from afar as secretary for International Initiatives of the Society for New Testament Studies, working with its Eastern European Liaison Committee. The Society was able to win the support of Metropolitan Hilarion for the event, who generously hosted us on behalf of the Russian church.

This was a major development in the opening up of the discussion of how New Testament scholarship relates to faith. Some whose faith is nurtured and sustained by the ancient Orthodox liturgical tradition have been reluctant to look beyond it to the world of New Testament scholarship; to ask questions about history and identify diversity, as well as unity among the New Testament writings might undermine faith. We know such fear also from western fundamentalism.

The opposite stance sees faith as the basis for openness to explore, in the confidence that God is also present in the arena of scientific research. In initiating this openness, Metropolitan Hilarion also issued a challenge to New Testament scholarship to avoid damaging and delusional extremes.

The opposite stance sees faith as the basis for openness to explore, in the confidence that God is also present in the arena of scientific research. In initiating this openness, Metropolitan Hilarion also issued a challenge to New Testament scholarship to avoid damaging and delusional extremes.

What emerged from our discussions was a clear sense that the differences are not primarily between east and west, but more diverse. Stereotypes, often conjured by politic concerns, are to be avoided. Faith makes claims about history and so cannot run away from its uncertainties and ambiguities. There are no ‘short cuts’ for faith. Faith need never fear to ask questions.

I stood through three full-length (three hour) liturgies celebrated in the ancient Slavonic tongue, sung or chanted by powerful, deep voiced males and accompanied by beautiful, mixed a cappella choirs. An aesthetic experience in itself, this was also the way faith is expressed and nourished in this tradition.

It was clearly engaging for the worshippers as they came and went, despite their not knowing Slavonic, recalling the days of the Latin mass. We found the beginning of a way to communicate despite our strange and diverse spiritualities.

It was a commitment to listen and ultimately a commitment to love.

William Loader