As we move towards Christmas we think about the coming of Jesus. The baby Jesus was born in Bethlehem in a

stable. Many people and churches have nativity scenes, which goes back to a practice started by Francis of Assisi in the thirteenth century to help people recognise the significance of God becoming a baby born among us in Jesus.

In theological terms we speak of the incarnation; God became human in Jesus. John’s gospel puts it in lofty terms, “the Word became flesh and lived among us.” God’s Word, the logos, became a person in Jesus. Theologian John Macquarrie suggests the incarnation is ‘inhumanisation’ meaning the same thing, namely God taking on being a human in Jesus, God’s Son.

Jesus is the central figure of Christmas.

Mary also features prominently. She is told by an angel she will give birth to the son of God and humbly submits. In two of the gospels, namely Matthew and Luke, she is described as a virgin who gives birth to Jesus through the Holy Spirit. The virgin birth is not mentioned by Mark, Paul, John or any of the other New Testament writers.

Nevertheless, Mary became known as the Virgin Mary and this is given prominence in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds in which “born of the Virgin Mary” is a key phrase.

In the fifth century, reverence for Mary grew and the term ‘theotokos’ meaning bearer or mother of God became common. One person who was not happy with this development was Bishop Nestorius at Constantinople. He argued against it asking, ‘Does God have a mother?’ It was not a good move by Nestorius who offended both common people and other theologians such as Cyril of Alexandria who opposed him.

The term ‘theotokos’ or ‘mother of God’ was officially affirmed by a council and became accepted in Catholic tradition. Protestants at the time of the Reformation, however, rejected it. Nevertheless, in recent times Protestants have valued Mary especially with the influence of feminist theology which draws attention to women in the Bible.

Joseph, however, is not given much attention.

He deserves more. In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus’ genealogy as Messiah is traced back through David to Abraham via Joseph. When Mary’s pregnancy was explained by an angel in a dream, Joseph accepted it. He was intending quietly to break his engagement to her for he was, we are told, a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace.

In first century Jewish culture it would have been understandable that he would break the engagement and send her away. He would have been somewhat older, working in a trade, and therefore in a position readily to attract a wife.

He was not just a self-respecting Jew who was known in the village and in the synagogue at Nazareth, but a righteous person. He took his faith seriously and lived according to the Jewish law. He understood himself to be one of the chosen people, conscious of his ancestry going back to David.

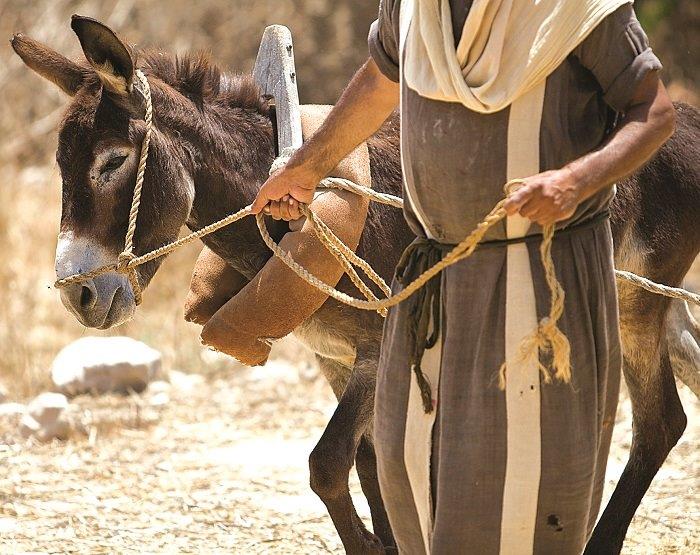

That was why he took Mary to Bethlehem, the city of David, for the Roman census. He was also astute. When he heard of the intention of King Herod to kill recently born children, he quickly took Mary and Jesusto Egypt to escape, not returning until it was safe to do so.

We can assume he was a good father to Jesus, encouraging him in his faith and development. Jesus took over the family carpentry business it seems for he was known as a carpenter. While we do not know when Joseph died, it was before Jesus began his public ministry.

Joseph was remembered. When Jesus went to Nazareth and preached in the synagogue, the people said, “Is not this Joseph’s son?” May we too remember Joseph this Christmas as Jesus’ earthly father. He is an important part of the story also.

Rev Dr Chris Walker