From Thursday 18 June to Friday 17 July, our Muslim friends will be celebrating Ramadan. Our non-Muslim readers may be wondering ‘What does that have to do with me?’ In a multicultural, multi-religious society, it’s all too important to move beyond our circles to love and understand those we might normally walk straight past.

As one of the biggest events in the Islamic calendar, Ramadan is an important time for people from the Islamic faith. Even though Muslims only make up 2.2% of the Australian population, there is a lot of fear in the community at the moment as we hear stories about extremists and terrorists around the world. It is right to abhor these events, but it is also right to work towards building strong relationships with people from all faiths. Most Muslims themselves disapprove of these acts, which go against the teachings of Islam.

While this year, Ramadan is taking place in June, the event is based on the Islamic Luna Calendar and so, like Easter, moves date each year. Muslims believe that their holy book, the Qur’an, was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad during this month, so it is a holy month which is full of God’s blessings. Traditionally, many Muslims also believe that during the month of Ramadan the gates of heaven are opened, and the gates to hell are closed – so it is a time where people are encouraged to get closer to God.

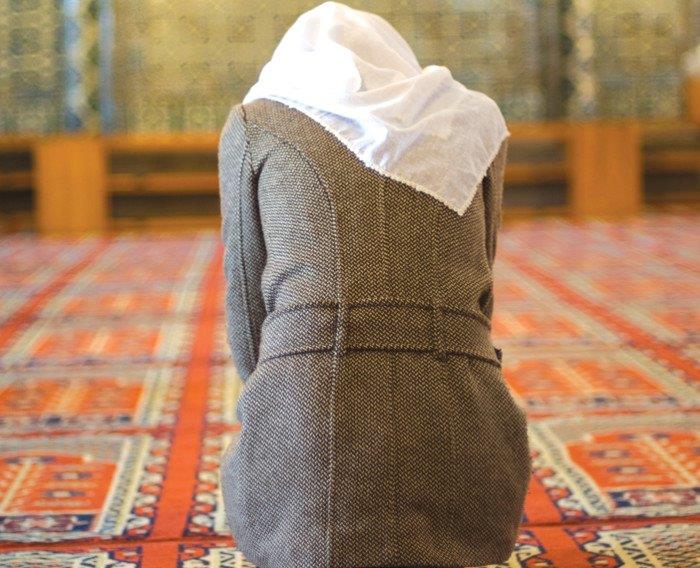

Muslims take up this opportunity in a range of ways, the most common being fasting.

Fasting during Ramadan occurs from before the sun rises, to after the sun has set each day and is a fast of all food, liquid and sexual relationships. Muslims participating in Ramadan will wake before the sun for morning prayers and eat a moderate meal before beginning their fast. At the end of the day, friends and family will gather for an ‘Iftar’ dinner, which breaks the fast and brings people together to celebrate blessings of the month of Ramadan.

Fuat Layic is the president of the Intercultural Harmony Society, an Islamic organisation in Perth which promotes interfaith dialogue and harmony. He said that Ramadan is a time for self-discipline and a time for giving – many Muslims will use the time to increase their giving to charity and will reflect on their treatment of others.

“There is a focus on the soul and not on the physical side of the body,” said Fuat. “The person is cautious that [they are] fasting,” said Fuat. “So [their] dealings with people are important. It’s not just abstaining from food and your physical things, but also a time of becoming more cautious of yourself and how the person acts. I think fasting helps that. It’s a time for self discipline.”

For those of us who have never taken part in such a fast, it sounds uncomfortable and even painful. Fuat explains that, while it can be hard, it is a humbling experience which results in focussing the mind towards pleasing God and being thankful for all that we have.

“What does an apple cost, for example,” he said. “It may be fifty cents but really it is priceless because… you try to put an apple together! You can’t put it together; it’s a God given thing. So, once you’re hungry and you have those sorts of thoughts and feelings, you appreciate and are really thankful for what God has given.”

Towards the end of Ramadan, in the final ten days, prayer and fasting becomes even more important. Muslims believe that, historically, the Prophet Muhammad lived at his mosque for those days, devoting himself to prayer and fasting. On a hidden night during this time is what is known as ‘the night of power’, which is believed to be the most valuable night during Ramadan. Muslims believe that if God is pleased on this night their sins will be forgiven, so the last ten days of Ramadan are the most important days to observe the religious festival.

Then, at the end of Ramadan, is the celebration of Eid. For three days, Muslims celebrate with friends and family. Fuat explains that this is not a celebration of being able to eat again, but a celebration that their sins are cleansed and that they have pleased God through their prayers, selfdiscipline and actions towards others.

“Its not a celebration that we’ve come out of Ramadan and the fasting has finished,” said Fuat, “Some people say we are celebrating because the fasting has finished and we can freely eat! It is bigger than that. The celebration is that the people are hopeful that they have pleased God and their sins may have been forgiven.”

Fuat said that there is a lot of joy that comes from taking part in Ramadan, such as community building and social gatherings, but that the main goal of taking part in the festival is the journey each person takes with God.

“It’s a pleasure that you have fulfilled the requirements of what God has prescribed for the person. That’s the ultimate joy that you will be getting out of it. You’re pleasing God.”

Of course, people’s devotion to their religion varies. Not all Muslims are strict on all of these activities, just as not all Christians live out the teachings of Jesus every day. How much a person takes part in Ramadan varies from person to person.

Rev Seforosa Carroll has been involved with the Relations with Other Faiths Working Group of the Uniting Church in Australia for a number of years, including being its chair. She believes that there’s a lot for Christians to learn by understanding Ramadan.

“The whole thing is about bringing that focus back to God, and in a world where we’re so cluttered, it is a good discipline,” she said. “That’s what they teach us Christians, that kind of disciplined practice of prayer and fasting.”

Apart from during Lent, most Christians don’t take part in fasting. But, it is a biblical concept.

“It is part of our tradition and one that I don’t think we utilise very much,” said Seforosa. “When you have a relationship with a Muslim, and as you get to know Islam more, you’re actually thinking ‘what does my own tradition of fasting and prayer teach me?’” Seforosa said.

In the Catholic tradition, Seforosa said that fasting is “a time of reconciliation, repentance and renewing.”

As part of his work with the Intercultural Harmony Society, Fuat helps organise community Iftar dinners, including the annual State Parliamentary Iftar Dinner. Community leaders are invited to large events and smaller home dinners to join in the breaking of the fast with those taking part in Ramadan.

Seforosa believes that building these kinds of relationships are vital for a healthy community.

“I think it’s [interfaith relationships] as important as breathing,” she said. “Because we can no longer ignore diversity or difference; it’s in our backyard even if we choose not to see it.

“It is at the very heart of our Christian discipleship and faith to actually live in good neighbourly relationship with the other. If we look at our Christian tradition, we’re always called to extend that hospitality to our neighbour. The call is not to the neighbour we know, that’s the easy part. It’s to the neighbour we don’t know.”

Inspired?

For more info on the Intercultural Harmony Society, contact Fuat Layic at fuat@harmony.org.au. You can visit their sister organisation’s website at http://www.intercultural.org.au/ to learn about the kind of work they do. The Australian Intercultural Society is based in Melbourne and are involved in similar work to WA’s Intercultural Harmony Society.

For more info on the Uniting Church in Australia’s Relations with Other Faiths Working Group visit http://assembly.uca.org.au/rof/

Heather Dowling